If you’ve been enjoying the work here, I’d love it if you considered becoming a paid subscriber. Your support helps me keep researching, writing, and sharing these ideas.

You can also leave a tip if you’d like — every bit helps and means a lot.

Thank you for reading and being here.

The impulse to create and venerate images is as old as civilisation itself. From the cave paintings of Lascaux to the golden icons of Orthodox cathedrals, art has long served not only as aesthetic expression, but as a bridge between human and divine, memory and myth, self and society. Across centuries and cultures, images have functioned as more than decoration. They have been conduits of belief, keepers of identity, and embodiments of power.

Yet running parallel to this creative instinct is another, equally primal: the desire to destroy these same images. Iconoclasm (literally “image breaking”) is not merely an act of violence or vandalism. It is often something more profound: a ritual, a reckoning, a rupture with the past in pursuit of a purified future. Why does the annihilation of an image—something that, on the surface, seems nihilistic—so often carry the weight of reverence? Why can a shattered icon, or even the bare space it once occupied, resonate more powerfully than the intact object ever did?

To answer this, we must understand that iconoclasm is not just destruction; it is a language. A visual, visceral way of expressing cultural crisis, revolutionary fervour, or spiritual renewal. It is a symbolic act, often carried out not in secret, but in public, with an audience. The iconoclast does not always seek to erase, but to transform: turning an object of worship into a stage for protest or purification.

What Is an Icon, and Why Break It?

An "icon" is more than just an image; it is an object that accrues symbolic weight, a vessel of shared meaning. In religious traditions, it may be imbued with divine presence; in secular societies, it can represent authority, ideology, or national identity. The destruction of such an object is never simply about aesthetics. It is a challenge to what the icon represents. It is an attempt to rewrite the visual language of power.

Iconoclasm is, at its core, a form of iconography in reverse. It seeks not to depict, but to erase. And yet, paradoxically, in erasing, it often creates new images—ones charged with defiance, trauma, and meaning.

The word itself derives from the Greek eikonoklastēs—“breaker of icons.” But this tidy etymology hides a more complex reality: iconoclasm is rarely an act of simple destruction. It is often a ritualised performance, a kind of visual theology or political theatre.

Byzantium: The Birthplace of Religious Iconoclasm

The earliest and most emblematic chapter in the history of iconoclasm unfolds in the Byzantine Empire. Beginning in 726 AD, Emperor Leo III launched what would become known as the First Iconoclasm. He issued a decree against religious imagery, spurred by theological concerns that icons violated the Second Commandment’s prohibition against graven images.

But this was not just a legal or doctrinal issue—it was spiritual warfare. Iconoclasts in Byzantium didn’t merely remove paintings or sculptures; they smashed them in sacred spaces, replacing human-made depictions of the divine with crosses, plain walls, or even nothing at all. The void became holy. This was not vandalism; it was reverence through subtraction. It was, in their eyes, a purging of spiritual corruption, a return to an unmediated relationship with God.

The controversy tore the empire apart. Iconophiles (those who defended the veneration of images) argued that icons were not idols but windows to the divine. To them, the destruction of icons wasn’t purification; it was desecration. Churches were split. Theological treatises were written in fire and stone. And though iconoclasm was eventually condemned at the Second Council of Nicaea in 787, the conflict would flare again in the 9th century. It left scars that would shape Orthodox Christianity forever.

The Reformation: Words Over Images

A thousand years later, the theological script flipped again, but this time in Western Europe. During the Protestant Reformation, iconoclasm became a hallmark of religious reform. Reformers like Ulrich Zwingli and John Calvin saw Catholic imagery, its saints, relics, and ornate altarpieces, as distractions from the true object of faith: the Word of God.

This was not just a change in theology—it was a transformation of the visual world. Churches were stripped bare. Stained glass windows were shattered. Crucifixes were ripped from the walls. The 1566 Beeldenstorm ("Iconoclastic Fury") in the Low Countries saw mobs of Calvinists tear through Catholic churches, toppling statues and smashing sacred objects. These actions were often framed as sermons—silent, forceful declarations of a new kind of purity.

But again, the motive was not simply destruction. It was a reorientation. Reformers weren’t attacking God—they were attacking what they saw as human distortions of divine truth. To break an image was to liberate the sacred from its visual cage.

Political Iconoclasm: Breaking Kings and Empires

Iconoclasm is not confined to religion. It arises wherever symbols are invested with power. During the French Revolution, statues of kings and saints were systematically destroyed. The logic was clear: if the monarchy was to fall, its visual scaffolding had to fall with it. The destruction of symbols became a kind of secular exorcism—a violent rebirth of the public square. In 1792, revolutionaries toppled the statue of Louis XIV in Place des Victoires; in 1871, the Vendôme Column, erected by Napoleon to celebrate military conquest, was pulled down by the Paris Commune as a statement against imperialism.

In these acts, the image of power became the battlefield of power itself.

Modern Iconoclasm: Memory, Protest, and the Politics of Space

In the 21st century, we have seen a resurgence of iconoclastic acts—not from the top down, but from the bottom up. The toppling of Confederate statues in the American South, or the dunking of slave trader Edward Colston’s statue into Bristol harbour, were not random acts of rage. They were deliberate, performative rejections of historical narratives. Protesters weren’t just attacking stone; they were dismantling myths.

Public monuments are never neutral. They sanctify particular versions of history, often privileging the powerful while silencing the oppressed. To remove a statue is to ask, loudly and visually: Whose story are we telling? And why?

This modern iconoclasm often spurs backlash—accusations of erasing history, of desecrating heritage. But to many, it is not erasure; it is revision. An attempt to reclaim space and memory from those who have monopolised it.

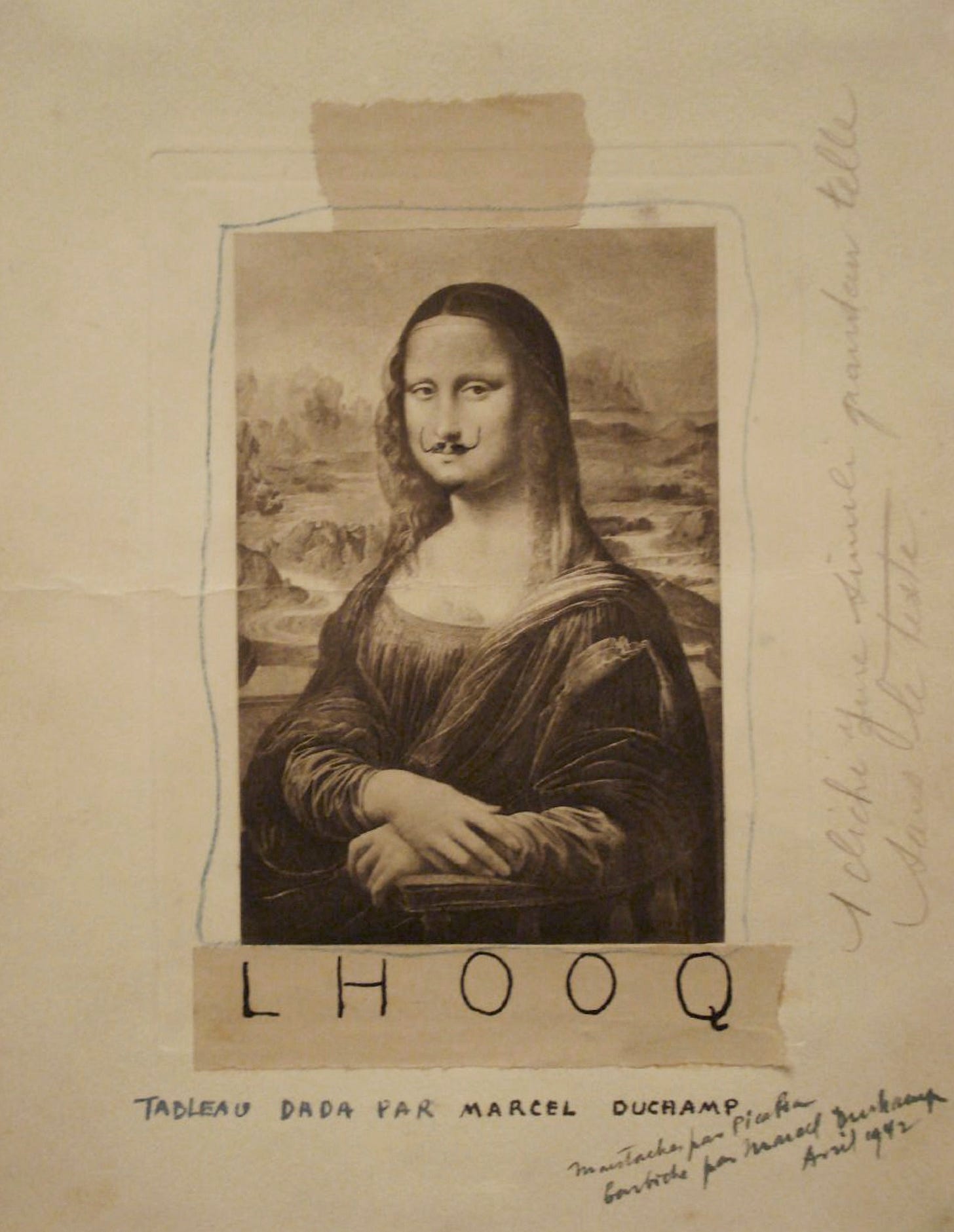

Iconoclasm has even found a paradoxical home within the world of art itself. The Dadaists, born in the chaos of World War I, rejected the bourgeois veneration of traditional art. Marcel Duchamp’s “L.H.O.O.Q.”—a cheap reproduction of the Mona Lisa with a moustache—was not just a joke. It was an act of aesthetic heresy, a provocation against the idea of artistic sanctity.

In these moments, iconoclasm becomes not the end of art, but its transformation. Destruction becomes the medium.

What remains after the image is gone? A blank wall. An empty pedestal. A photograph of the moment of fall. These absences can hold more meaning than the original ever did. The removal of an image doesn’t just mark an end: it marks a beginning. It becomes a canvas for new stories, new values, and new symbols. The absence itself becomes iconic.

Consider the Buddhas of Bamiyan, dynamited by the Taliban in 2001. Their destruction was a global shock. And yet, the empty niches where they once stood now possess a haunting, sacred gravity. The voids speak of loss, of memory, of what we choose to revere and erase.

In the end, iconoclasm is not always an act of hate. It can be an act of love—a love for purity, for truth, for the uncorrupted ideal. A desire to reach beyond the image, to the thing it only imperfectly represented. To break the image is, sometimes, to free it. We live in a time of image overload, where every moment is photographed, filtered, and shared. Iconoclasm reminds us that absence, too, has power. That the space left behind by a broken image can invite deeper reflection than the object itself.

A shattered statue. A scrubbed mural. A missing frame. Each one asks us: What did this mean? And what could it mean now?

In the fragments, we sometimes find the future.

gorgeous !!!!

This is so incredibly well written and gripping, thank you for this deeply profound and ever-relevant history lesson on a concept that I hadn’t heard of before. I can’t wait to read more of your wonderful pieces of writing <3