the enduring allure of trinket collecting

why humans have always loved small, collectible objects, and how sonny angels and smiskis fit into a centuries-old tradition

If you’ve been enjoying the work here, I’d love it if you considered becoming a paid subscriber. Your support helps me keep researching, writing, and sharing these ideas.

You can also leave a tip if you’d like — every bit helps and means a lot.

Thank you for reading and being here.

There’s something irresistible (at least, for me) about holding a tiny treasure in the palm of your hand.

Across thousands of years and countless cultures, humans have been enchanted by miniature objects. From ancient amulets worn close to the skin to modern figurines lined up neatly on bookshelves, we have always surrounded ourselves with small, meaningful things. These aren’t mere decorations. They are vessels of memory, expressions of identity, sources of comfort, and social signals of belonging.

Today’s exploding interest in Sonny Angels, Smiskis, Labubu, and other collectable art toys is not a quirky new fad; it’s a continuation of a long and surprisingly universal human tradition. Understanding why these modern miniatures captivate us so deeply requires tracing their roots back to the earliest trinkets ever made.

Ancient Roots

The first trinkets weren’t about fun, they were about survival and spirituality.

In prehistoric times, long before written language, humans fashioned small objects from animal bones, teeth, shells, and carved stones. These were not just ornaments but protective charms, believed to ward off misfortune, disease, or malevolent spirits. Worn around the neck or carried in pouches, these amulets were early attempts to exert control over an unpredictable world, blending spiritual belief with tactile craftsmanship.

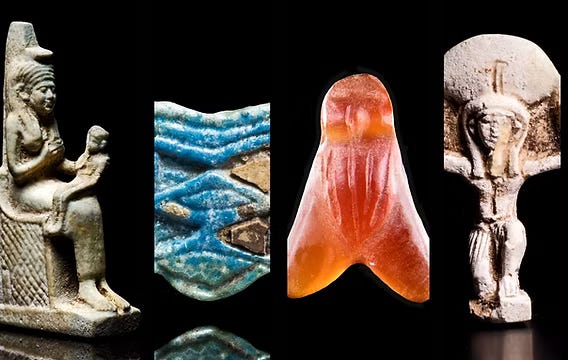

In ancient Egypt, this practice evolved into a highly sophisticated art. Egyptian amulets, often made from glazed faience, carnelian, or gold, were more than decorative tokens; they were spiritual tools with precise ritual functions. The scarab beetle, for instance, symbolised the sun god Ra and represented rebirth and eternal life. Scarab amulets were meticulously crafted according to instructions in the Book of the Dead and placed on the chest of mummies to ensure safe passage into the afterlife. Egyptians even made duplicate amulets, hedging their bets in case the first charm failed to deliver its promised protection.

This belief in the protective and symbolic power of small objects was widespread.

In the Roman Empire, discreet charms served as covert markers of religious affiliation. Early Christians carried small fish-shaped tokens (the ichthys) to secretly identify themselves to fellow believers. Jewish communities wore tiny golden capsules inscribed with passages from sacred texts, keeping their faith literally close to their hearts. During the Middle Ages, knights donned charms engraved with prayers or saintly images as spiritual armour in battle. Although Renaissance rationalism briefly dampened enthusiasm for such talismans, figures like Catherine de' Medici were famously rumoured to wear charm-laden jewellery imbued with occult significance, suggesting the old superstitions never fully disappeared.

Across all these eras, small objects functioned as powerful intersections of belief, identity, and community.

The Victorian Revolution

By the 18th and 19th centuries, the role of charms expanded from the spiritual to the autobiographical.

Women’s chatelaines (ornate waist-clipped chains holding keys, thimbles, and scissors) doubled as decorative showcases for sentimental trinkets. Men’s watch fobs, dangling from waistcoat pockets, often displayed tiny engraved seals, hobby symbols, or romantic motifs. These miniature ornaments quietly communicated details about their wearer’s profession, interests, or social ties.

It was Queen Victoria, however, who transformed charm collecting into a cultural phenomenon.

Her deep affection for personal mementoes popularised charm bracelets throughout Europe. One of her most famous pieces was a mourning bracelet adorned with sixteen intricately designed lockets commemorating her beloved husband, Prince Albert. Each charm contained a lock of hair, a miniature portrait, or a symbolic design marking their shared milestones. Another bracelet, celebrating her children, featured nine enamelled heart-shaped lockets in different colours, each inscribed with a child’s name and birth date, and containing a curl of their hair. These were not mere ornaments but wearable biographies.

Victoria’s influence democratised the charm bracelet, making it fashionable across all classes, especially as the Industrial Revolution enabled mass production of finely detailed silver and gold charms. Tiffany & Co. further cemented the trend with its 1889 debut of the now-iconic silver heart tag bracelet, which remains a status symbol today.

By the mid-20th century, charm bracelets had become a staple of young womanhood, particularly in England and the United States.

Girls would collect charms to commemorate birthdays, graduations, marriages, holidays, and travel adventures. Each charm added a new chapter to a highly personal, visual narrative. The beauty of the charm bracelet lay in its flexibility: no two were alike, and each evolved over a lifetime, mirroring its wearer’s journey. Vintage charm bracelets from this era, rich with hollow stamped charms, articulated trinkets, enamel designs, and mechanical motifs, are now highly collectable and not just for their craftsmanship, but for the unique life stories they encapsulate.

The Contemporary Revival

Today’s trinket collectors may not wear their treasures on their wrists, but the impulse remains remarkably similar.

The phenomenal success of Sonny Angels, created by Japanese designer Toru Soeya in 2004, offers a modern parallel to the sentimental charm bracelet. Originally envisioned as comforting desk companions for stressed-out working women in Japan, Sonny Angels feature cherubic baby-like figures with rosy cheeks, delicate angel wings, and whimsical headgear — everything from fruits and vegetables to sea creatures and seasonal motifs. Their compact size, sweet expressions, and endless variety have earned them a passionate global following, especially in the United States and East Asia.

Like historical charms, Sonny Angels offer comfort, surprise, and a means of storytelling.

Sold in blind boxes, collectors experience the same thrill of anticipation once felt by Victorian women unwrapping a newly gifted charm. You don’t know which design you’ll receive, and the rare, secret figurines heighten the sense of playful risk. This element of chance and discovery taps into deep-rooted psychological pleasure centres, blending nostalgia, novelty, and mastery.

Sonny Angels are not alone. Other collectable art toys, like the glow-in-the-dark Smiskis (depicting tiny figures in everyday poses) and figurines from Pop Mart (featuring characters like Labubu and Molly), feed a similar hunger. Collectors proudly display their finds on shelves, desks, or in shadow boxes. Some transform them into keychains or photo props, integrating them into daily life much like Victorian women once integrated charms into their attire. Online communities facilitate trading, sharing, and showcasing collections, replicating the communal aspect that ancient charm wearers and Victorian collectors alike enjoyed.

Why We Keep Collecting

The enduring human fascination with small collectables is rooted in multiple psychological drives, and each one helps explain why we continue to seek, display, and cherish these miniature items.

First, collecting offers a sense of control and mastery.

In an unpredictable world, the structured pursuit of completing a collection — whether it’s assembling a full bracelet of charms or hunting for a rare Sonny Angel — provides a reassuring sense of order and accomplishment. The act of curating, categorising, and displaying a set engages cognitive skills we instinctively enjoy.

Second, collectables act as memory anchors and emotional touchstones.

Like Queen Victoria’s lockets of her children’s hair, modern trinkets can mark meaningful life events or phases. A Sonny Angel unboxed on a birthday trip, or a Labubu traded with a friend, carries emotional resonance long after the object itself is acquired. Such tokens quietly record personal history.

Third, these objects provide comfort and companionship.

Research shows that tactile interaction with familiar, sentimental objects can reduce anxiety and boost feelings of security. This is not limited to childhood plush toys; adults, too, find solace in small, comforting items, be it a vintage charm bracelet or a glow-in-the-dark Smiski tucked on a nightstand.

Finally, collectables are expressions of identity and belonging.

What we choose to collect, and how we curate or display our collections signals who we are and invites connection with like-minded individuals. In ancient Rome, a hidden fish charm revealed religious affiliation. In the Victorian era, a bracelet charm hinted at a woman’s life milestones. Today, a shelf of Sonny Angels or Pop Mart figurines may indicate aesthetic taste, cultural interests, or membership in a global collector community. As researchers note, many of us view treasured small objects not just as possessions but as extensions of self, not mine but me.

Small Things, Big Meaning

From scarab amulets nestled in Egyptian tombs to Sonny Angels perched on modern bookshelves, humans have always imbued small objects with outsized meaning. These trinkets, whether fashioned from bone, gold, or plastic, serve as compact vessels of memory, identity, comfort, and connection.

While materials and aesthetics evolve across centuries, the fundamental impulse remains remarkably stable: we collect to tell our stories, to feel anchored in our lives, to find companionship, and to connect with others. The Victorian charm bracelet and the Pop Mart blind box share more DNA than one might expect. Both invite us to curate miniature autobiographies, rich with symbolism and sentiment.

In a world that often feels transient and digital, perhaps it’s no surprise that tangible, tactile tokens retain such appeal. Tiny treasures remind us who we are, where we’ve been, and (perhaps most importantly) that even the smallest things can carry the biggest meanings.

you had me at trinket

Humans yearn for trinkets and I think that’s beautiful