vulva imagery in religious and medieval art

when the Divine Feminine was hiding in plain sight...

If you’ve been enjoying the work here, I’d love it if you considered becoming a paid subscriber. Your support helps me keep researching, writing, and sharing these ideas.

You can also leave a tip if you’d like — every bit helps and means a lot.

Thank you for reading and being here.

For millennia, the image of the vulva held a profound, often hidden, significance in human culture, from prehistoric carvings to medieval curiosities and even influenced the symbols of major world religions. What was once a revered symbol of creation and female power has been obscured and sometimes deliberately erased by patriarchal dominance. Yet, traces of this potent iconography persist in religious and medieval art, offering a fascinating glimpse into the complex relationship between the human body, spirituality, and societal beliefs.

The vulva stands as one of the oldest and most common subjects in prehistoric art. Across the globe, from the sandstone walls of Carnarvon Gorge in Australia, known as "The Wall of One Thousand Vulvas", to cave paintings in France and Spain, our ancestors etched and painted images of female genitalia tens of thousands of years ago. Scholars suggest that early humans, without a clear understanding of the male role in procreation, recognised the unequivocal power of women to bring forth life, making the vulva a primary object of devotion and an invocation of this creative force. Female bodies and their life-giving capabilities were the focus of profound reverence for a period vastly longer than recorded history.

This veneration of the vulva and female sexuality continued into ancient civilisations. In Sumer, over 7,000 years ago, the goddess Inanna celebrated the beauty of her genitals in hymns. The central rite of Sumerian religion involved the high priestess, representing Inanna, and the king, enacting a sacred union focused on the "holy vulva of Inanna" to stimulate fertility. The very word 'venerate' stems from the Latin venerari, linked to veneris, meaning love and sexual desire, from which the name Venus is derived. Even today, traditions like yoni puja in India consider the vulva a portal to the divine.

With the rise of patriarchal cultures around 5,000 years ago, men began to assert control over women's bodies and sexuality to ensure patrilineal inheritance. This shift led to the obscuring and denigration of the vulva's once-sacred status. However, such a powerful and universal symbol could not simply vanish.

Intriguingly, the seemingly patriarchal Abrahamic faiths also bear traces of vulvar symbolism. Some scholars suggest that the vulva of the Hebrew goddess was represented by water in ancient Jewish temples, and the Kaaba in Islam, once sacred to the goddess Al'Lat, is enshrined in a silver vulva touched by pilgrims.

Perhaps more surprisingly, Christianity, despite its male-dominated hierarchy, appears to have assimilated and transformed yonic imagery for its own purposes:

The Ichthys (Jesus Fish): Jon Katz reveals the controversial idea that the ichthys, or "Jesus Fish," one of Christianity's most beloved symbols, may have originated as a pagan symbol for the vulva. Turned sideways, the shape bears a striking resemblance. This symbol was associated with pre-Christian fertility goddesses like Atargatis, Aphrodite, and Artemis. The founders of Christianity may have adopted pagan symbols to attract new converts. Notably, Atargatis was a fish goddess, and ichthys is the Greek word for fish.

In Christian art, especially during the medieval period, both Jesus Christ and the Virgin Mary are frequently depicted within a radiant, almond-shaped oval known as a mandorla or vesica piscis. This shape, scholars argue, is distinctly inspired by the vulva, representing cosmic creation and the primordial womb. The Virgin of Guadalupe's image, which gained prominence after the 16th century, is consistently framed by a mandorla of golden light, with her flowing robes resembling labial folds. Mary is thus depicted as the "tunnel" through which God entered the world.

Medieval Christian prayer books often feature surprisingly visceral depictions of Christ's Five Holy Wounds, particularly the wound in his side caused by the Lance of Longinus. These fleshy, brightly coloured depictions can evoke the shape of a vulva. Scholars speculate that the slit-like wound emitting blood and fluid led some mystics to draw parallels with female bodily openings and fluids like breast milk, menstrual blood, or amniotic fluid, connecting Christ's resurrection to life-giving female reproduction. The tradition of depicting Christ as a motherly figure, even showing figures being birthed from his side wound, emerged during the rise of female mystics. Some even argue these depictions represent a gender fluidity of Christ.

While Christian art subtly incorporated yonic forms, the medieval period also saw more explicit, albeit sometimes enigmatic, depictions of the vulva:

From the 12th century onwards, Sheela-na-gigs were found carved into the walls of Irish and British churches, castles, and other buildings. They are figurative carvings of naked women displaying an exaggerated vulva. Often positioned above entryways, they are believed to have originated from European Indigenous pagan religions and may have served an apotropaic function, warding off evil spirits. The church later demonised them as witches and pagan goddesses.

Medieval pilgrims wore badges as tokens of devotion. Among these were profane or obscene badges with sexual imagery, including explicit depictions of the vulva, sometimes alone or in conjunction with phalluses. These badges, dating from the 14th through 16th centuries, have puzzled scholars, with interpretations ranging from satirical commentaries on women, marriage, or pilgrimage itself, to potential symbols of female empowerment and fertility. Some badges depicted a "Vulva Pilgrim," an anthropomorphised vulva wearing pilgrim attire like a hat and carrying a staff (sometimes topped with a phallus) and rosary beads. These may have satirised the figure of the female pilgrim, who was sometimes viewed with suspicion and associated with social disorder. The inclusion of pattens (clogs worn outdoors) on some Vulva Pilgrim badges further emphasised their public presence, contrasting with the expected private life of women. The gender ambiguity in some of these badges, with vulvas possessing phallic attributes, could reflect anxieties about social and gender boundaries in a time of significant social change. The context of the late medieval Carnival, a period of social inversion and bodily excess, may have made the wearing of such graphic sexual insignia acceptable as a form of social commentary.

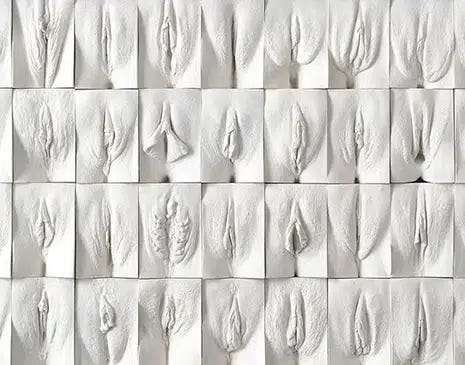

While historical and religious art often coded or subtly incorporated vulvar imagery, contemporary art sees a deliberate and explicit reclamation of this powerful symbol. Artists, particularly feminist artists since the second wave, have challenged the historical erasure and negative connotations surrounding female genitalia. From Judy Chicago's vulva-themed "Dinner Party" to more recent works like Jamie McCartney's "Great Wall of Vagina" celebrating vulvar diversity and Janelle Monáe's "Pynk" video featuring vulva trousers, artists are bringing the vulva front and centre, exploring themes of female sexuality, power, and challenging societal norms. Even Marian vulva imagery is being reclaimed in contemporary art, complicating traditional notions of Mary's sexuality and divinity.

Understanding the long and often hidden history of vulva imagery in religious and medieval art reveals a fascinating story of reverence, repression, and eventual reclamation. It highlights the enduring power of this primal symbol and its capacity to embody fundamental concepts of creation, fertility, spirituality, and the ever-evolving dynamics of gender and power throughout human history. Recognising these yonic forms in art allows us to see beyond conventional interpretations and appreciate the rich, often subversive, layers of meaning embedded within these visual representations. It also reminds us of the importance of understanding the distinction between the vulva (the external female genitalia) and the vagina (the internal canal), a distinction that continues to be relevant in discussions of female anatomy and representation.

What might our world look like if we returned to honouring the vulva not with silence or shame, but with the reverence our ancestors once held—for its power to create, transform, and connect us to the divine?

hii fascinating piece! do you happen to have any good articles/books about the symbolism of Christ’s side wound and its connection to feminity that you wrote about? would love to write about it in my master’s thesis about teresa starzec’s art!!🫶

I’m reading every word like it’s a secret map — “When the Divine Feminine was hiding in plain sight...” you caught it so sharply. The way Christ’s side wound becomes a symbol, the mandorla, the Vulva Pilgrim — it’s brilliant and sly. You weave ancient reverence and sly rebellion so artfully, it’s impossible not to think twice after every line. Great read Toni!